- Legend

- About

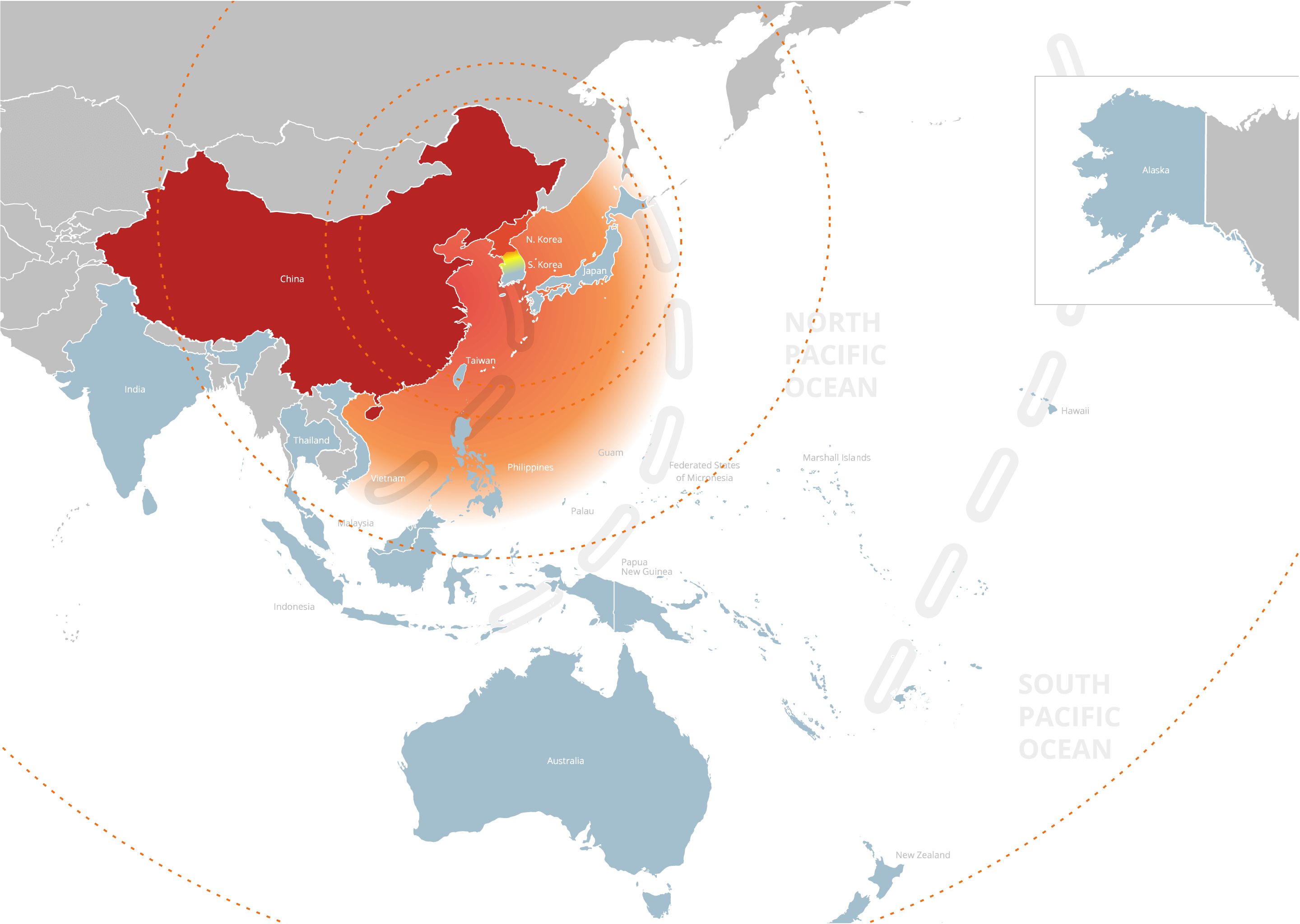

Current U.S. Force Posture

This map layer depicts the current U.S. force posture in the Indo-Pacific. U.S. force posture in the region constitutes of a mix of Cold War-era basing arrangements concentrated in Northeast Asia and a focus on expeditionary power projection to meet the challenges of the War on Terror.

The majority of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific are located in Northeast Asia. Beyond Northeast Asia, the United States maintains access to a diffuse array of smaller bases and logistics facilities. Many of these agreements allow for brief U.S. military rotations but lack the supporting infrastructure or political arrangements for long-term exclusive use, especially in wartime. As such, the southern half of the Indo-Pacific suffers from a relative lack of access for the U.S. military, particularly along the periphery of the hotly disputed South China Sea.

Perhaps most crucially, the majority of U.S. forces, bases, and assets in the Indo-Pacific lie within range of Chinese anti-area/access denial (A2AD) capabilities and North Korean conventional and nuclear weapons. This places U.S. forces at an increasing level of risk, thereby raising questions about the effectiveness of U.S. forces in Northeast Asia during a major, high-end conflict with China. As North Korea continues to expand its nuclear and conventional arsenals, and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) modernizes and grows more capable, the current model of U.S. force posture in the Indo-Pacific must adapt.

Introduction

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States military has grappled with threats around the world ranging from a rogue North Korea to two decades of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency in the greater Middle East. Under such a diverse range of mission sets and a diffuse threat landscape, U.S. force posture has come to involve a mixture of Cold War-era basing arrangements in Northeast Asia and a War on Terror emphasis on expeditionary power projection in the Middle East—all to the detriment of U.S. security commitments in the Indo-Pacific.

With the rise of China to near-peer competitor status, a still-intransigent and increasingly capable North Korea, and the growing salience of great power competition in the 21st century Indo-Pacific, this force posture model is increasingly unsuited to the demands and challenges facing the United States. Furthermore, new technologies threaten to undermine traditional areas of military advantage, while offering the U.S. military new opportunities that will have significant implications for force posture. Amidst these issues, there is genuine concern on the part of some policymakers and the general public as to the sustainability of a large, forward-deployed military presence in the Indo-Pacific.

This naturally raises some critical questions for American planners and policymakers about the implications of a rapidly changing military and geopolitical landscape for U.S. force posture in the region, and how the United States can continue to pursue its interests in a way that is both militarily effective and economically- and politically-sustainable.

“Postured for Victory”, a study by Abraham M. Denmark, Director of the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, and Lucas Myers, a Program Associate with the Asia Program, intends to address these question head on. This study examines the most significant challenges facing the United States in the Indo-Pacific, identifies key elements required of an effective and sustainable force posture, and proposes options for U.S. force posture in the Indo-Pacific that reflect the challenges and opportunities the United States will face in the coming decades.

This interactive map is intended to complement the report's findings. On the top right-hand portion of the screen, you will find a series of four map views. The first view, “Current U.S. Force Posture,” presents the U.S. military’s force posture in the Indo-Pacific as of 2021. The second view, “Offshore Balancing,” depicts an alternative proposal to a forward-deployed presence in the Indo-Pacific. The third view, “Postured for Victory,” presents the revitalized force posture described in the report. Finally, the fourth and fifth layers explore the region’s security architecture, much of it established during the Cold War.